Insight plextek

It's Time to embrace

open innovation

in uk defence

Many sectors are already harnessing the power of open innovation, but the UK’s defence industry seems to lag behind. Plextek chief executive Nicholas Hill explains the benefits of open innovation for defence manufacturers and highlights examples of successful collaborations.

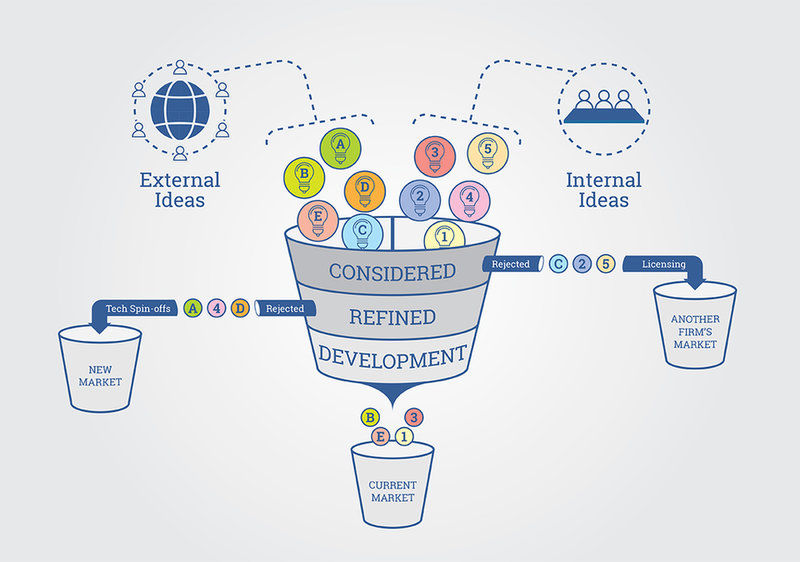

Open Innovation (OI) is much talked about in the media, and rightly so, as it has the potential to enhance our economy. The traditional innovation process, particularly in large companies, is typically shown as a funnel. At the mouth of the funnel a multitude of ideas are internally generated. Further down the funnel they are considered, refined and filtered down, reducing in number until just a few are left within the pipeline for product development. These are the ones with a business case that supports the investment necessary to complete the development.

Ideas that didn’t make it through the process are cast aside, perhaps because the technology wasn’t deemed credible, or because the potential market didn’t fit the business, or because the return on investment wasn’t adequate. The key point is that all of this is internal to the organisation, and the route in or out of the funnel is at the end, when a product is put on the market.

In an OI process this funnel is opened up, principally so that ideas or technology can be pulled into the funnel from outside. This often involves a relationship between a large organisation wanting to pull ideas or technology in, and a small organisation with ideas or technology to offer. However, OI includes modifying the process so that ideas or technology that had some potential but were not suitable for the core business can be spun out, sold off or otherwise turned into value, rather than being cast aside.

“

however large and great you are as an organisation, you don’t have a monopoly on the best ideas."

For me, true OI involves the two organisations working closely together throughout the process, from idea to marketable product, in contrast to the larger organisation simply subcontracting parts of the process, the ideas generation let’s say, to other companies.

There are several potential benefits of OI to the large company, but those most commonly quoted are faster time to market, access to new technology, access to additional competencies, and access to new ideas. These benefits come from a number of factors. For example, however large and great you are as an organisation, you don’t have a monopoly on the best ideas. And from the perspective of time to market, smaller organisations will usually work at a much faster pace, and this can be leveraged by the larger partner.

There’s also an inherent benefit in an organisation exposing itself to external ideas, including generating for new directions that couldn’t have been foreseen or planned, or serendipitous connections or interactions.

defence lags behind in open innovation

Open innovation is well established in certain sectors, with many fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies, for instance, having well developed OI programmes. The fast pace and constant need for new product ideas in FMCG provides a strong driver for OI.

But what about the UK defence industry? Study evidence suggests the sector is lagging behind in adopting OI, and the findings align with our own experience of providing innovation-related services across a range of sectors. Examples of OI programmes in the UK defence industry are very thin on the ground. Why would this be?

One factor is that the defence industry has traditionally had very long product or system development cycles, and very long service life. If innovation proceeds at a slow pace, this has not been a major problem. The government has a major influence in defence, for example providing a lot of early-stage technology-push funds.

Large companies can use these to investigate and progress their own ideas rather than looking externally, and may well be working at capacity to support pursuing them, together with those funded by internal R&D budgets. An additional layer of confidentiality burdens many defence projects, which naturally impedes external communication.

“

One of the interesting findings of OI studies is that R&D and product development functions top the list of departments which have the strongest cultural clash with an OI approach."

Defence as an enterprise is also highly tiered, so many products are integrated into larger products and systems, then systems-of-systems, and this inevitably means very large organisations sit at the top of the pyramid: organisations for which a fast, agile innovation process is not a key driver. These companies typically house strong internal R&D and product development functions. One of the interesting findings of OI studies is that R&D and product development functions top the list of departments which have the strongest cultural clash with an OI approach.

There is the classic ‘not invented here’ attitude, which can be hard to overcome, and can even exist within different parts of the same organisation. From an R&D group perspective, does OI reduce our ability to influence the direction of the organisation’s technology? Does it mean we could be reduced in size if the purchasing department decides to source more technology in from outside? What if the small company we are working with goes out of business next month?

There are many perfectly reasonable concerns and risks to consider, but the defence industry cannot afford to avoid OI for much longer. The pace of technology development in other sectors, including consumer, communications, IT and automotive has been accelerating hard and continues to do so. Defence does not operate in isolation and needs to keep pace with the rest of the world of technology, either because technology from elsewhere needs to be integrated into defence systems for them to be cost effective and credible, or because an enemy is using technology from other markets to create a threat.

Success factors for open innovation

Examples of OI can be found in the UK defence industry, although some organisations are more open than others. There are cases where a large organisation has set up an innovation ecosystem to promote close collaboration with a group of universities and SMEs. This will undoubtedly offer some of the benefits of OI, and removes some of the risk because the large organisation is only opening up to carefully selected, trusted partners. However, I would question whether such constraints in external engagement allow the full potential of OI to truly develop.

The best example of OI that we have seen is the SpaRk initiative run by Raytheon UK. Through this scheme Raytheon has launched a series of challenges to the widest possible audience, based on a number of themes. Winners are selected from each challenge and a modest contract is awarded to allow initial exploration of the idea. If the idea or technology continues to be promising, further rounds of funding are available.

The initiative is run by a dedicated OI group that was set up for the purpose, and which has the necessary budget and autonomy to succeed. Based on our experience of engagement with SpaRk since it was set up, we can identify a number of factors that are important to successful OI. Firstly, there must be a mutual culture of collaboration across both organisations. This is not a buyer-supplier relationship, even though money may be changing hands. Everyone must feel that they are working for a mutually agreed, common goal.

Illustration of the open innovation concept.

Inevitably, there will be times when the relationship is strained, and this is where another key element is required – a project champion in the large organisation who not only keeps their team on side but also develops a very close, trusted and trusting relationship with the smaller company and brings everyone together when things get difficult.

The OI team in the large company needs to be organised so that it can keep pace with the smaller organisation. Existing internal processes such as contract development, purchasing, sign off and authorisation are likely to be too slow, and dedicated processes are needed. Any commercial arrangement in this space must allow for the risk of failure during the project. If the outcome is certain, the project probably isn’t innovative enough.

“

One of the major worries I hear from SMEs when faced with the prospect of working with large defence companies is around lack of trust relating to IP – will they steal our best idea and develop it themselves?"

A clear policy on intellectual property (IP) is needed so that both sides know where they stand. This is not necessarily easy when the work is very speculative and novel, and the long-term outcome is unknown. However, it does need to be put to bed.

One of the major worries I hear from SMEs when faced with the prospect of working with large defence companies is around lack of trust relating to IP – will they steal our best idea and develop it themselves? Associated with this is the imbalance of power in the organisations. If this were a supplier-buyer relationship, the buyer would exert their terms and conditions, because they can, and they would often be very unfavourable to an SME. The contract terms for OI need to be drawn up in a very different spirit.

Finally, the interface between the OI unit and the rest of the business needs careful thought. You might compare the OI unit to an off-road vehicle roaming the landscape freely, following whatever direction seems promising. The main business units of the same organisation are more like railway tracks, well engineered to focus on a prescribed outcome and deliver it. There will come a point when the former needs to get onto the latter, as the OI unit hands over the project to what is now a new line of business. If that is not carefully thought through, the OI unit could simply be moving the boundary of the problem from the external interface to an internal one.

How can we embrace open innovation in the UK defence industry?

The UK defence industry needs to embrace OI, not only to remain cost effective and credible by incorporating the best ideas and technology from the widest possible pool, but also to ensure that we have a defence against threats relating to technology developed in other sectors.

Any large defence organisation that does not have an OI process should be thinking about how to set one up, and could do worse than looking closely at the Raytheon SpaRk initiative.

The government could usefully explore means by which technology-push funding could be used to encourage open innovation, rather than just competition, between large companies, SMEs and universities.

For SMEs anxious about the prospect of engaging with large defence companies, bear in mind that they command prodigious resources and determination, which could be applied to the exploitation of your next idea.